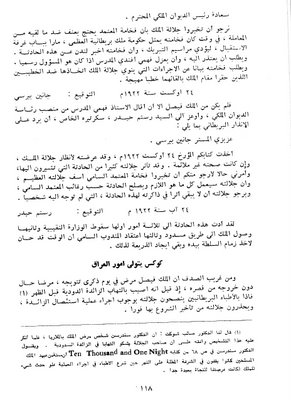

The Book Cover and pages 118 and 323 of Abdur-Razzaq Al-Hasani's

book, "ta'reekh al-wizaraat al-Iraqiyya" providing the

date of King Faisal I's appendectomy in August 1922 (page 118) and the date of

the King's death and who accompanied him to Switzerland (page 323).

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

IRAQ History E-Newsletter

Bi-Monthly

April 2006

April 2006

Inside This Issue

1. Iraqi Society During the Late Ottoman Era

By Anees Al-Qaisy

2. Iraq's Kings and Leaders Part 1

http://iraqshistory.blogspot.com/2006/01/kings-presidents-last-jews-in-baghdad.html

3. Iraq's Kings and Leaders Part 2

http://iraqshistory.blogspot.com/2006/02/iraq-kings-leaders-ii-announcements.html

4. Iraq's Kings and Leaders Part 3

Compiled and Translated by Wafaa'

5. Important Announcements

6. Acknowledgement

6. Acknowledgement

(*_*)

1. Iraqi Society During the Late Ottoman Era - Characteristics, Loyalties and Perspectives

By Anees Mahmood Al-Qaysi,

Faculty of Arts, History Department, University of Baghdad

anisalkaysi@yahoo.com

This study focuses on the important topic on whether Iraq, in its distinct demographic constitution, was similar to the states of the Arab east, namely Syria and Egypt, which were witnessing an intellectual and national awakening during this period?

This study focuses on the important topic on whether Iraq, in its distinct demographic constitution, was similar to the states of the Arab east, namely Syria and Egypt, which were witnessing an intellectual and national awakening during this period?

During the later Ottoman era, Iraqi society of a distinct nature, given that it was varied in its religious and ethnic makeup. There were Moslems, Jews, Christians and other religious groups, and there were also Kurds, Turkmans and other ethnic groups. This religious and ethnic composition impacted the crystallization of the Iraqi culture. It may be attributable to the policy followed by the Ottoman state towards the various segments of the Iraqi society.

The Ottoman state, as is known, relied upon the Sunni segments of Iraqi society. It allowed them to establish schools and to obtain state positions and to serve in the army. Hence, they had a greater opportunity than the Shiites in holding important state posts due to their support for the Ottoman state, which in turn availed them of the opportunity to get a better education. In effect, they dominated intellectual life and got the lion's share of governmental positions. The pan-Islamic policy of Sultan Abdul Hameed II contributed to strengthening this privileged position among the Sunnis, whose aim was to reinforce allegiances to the Ottoman state, while the Shiites who were districted from governmental positions and were prevented from opening schools. The Ottoman state did not recognize the Shiite religious authorities. This contributed to the increase in the rate of illiteracy among Shiites and the prevalence of superstitious beliefs, in contrast with the Sunnis who had a better education and so were secular in appearance and were Ottoman in culture. This policy led to a great increase in the role of the Shiite mujtahids (jurists) in Iraq, a majority of whom was of Persian orientation. They provoked both the Iraqis and the Ottoman state.

As for the remaining segments of the Iraqi society, such as Jews, Christians and others, they enjoyed special privileges in accordance with the Ottoman reforms and, also, in accordance with the foreign privileges. This led to their becoming autonomous in their religious and judicial affairs. The Jewish population focused on banking and economic activity, while the Christians focused on owning land and other properties, and they had schools, which were supported by western missionary institutions.

Iraqi society was and still is religiously and ethnically diverse. Although this diversity is for the most part positive and it did not prevent the flourishing of cities like Baghdad, Najaf, Karbala and Basra, Iraqi society remained non-cohesive, which made the penetration of western cultural and commercial interests in Iraq abundantly possible, and in turn deepened the rift between the segments of Iraqi society.

After the Turkish coup d'etat of 1908, the concept of Turkification, which was pervasive in Iraq, was substituted for the concept of Ottomanism. In fact, Turkification was the main impulse for the emergence of Arab nationalist movement (Qawmeyyah) in Iraq prior to World War I. However, this movement was exclusively restricted to the Sunni segment that was supportive of the Ottoman state. As for the Shiite segment of the population, it had a national sentiment (Wataneyyah) more than a pan-Arab feeling. This was clearly displayed in the 1920 revolution.

In brief, Iraq was not a favorable environment for the emergence of the nationalist idea as was the case in Syria and Egypt.

Note: This is an abstract from a 35-page study entitled, "Iraqi Society During the Later Ottoman Era: Characteristics, Loyalties and Perspectives"

4. Iraq's Kings and Leaders Part 3 - Compiled and Translated by Wafaa'

The era of King Faisal I was featured in part 1 of this series. The information later sparked a prolonged debate among few Iraqis about some of the puzzling and unknown aspects of his life and especially his death. In this part of the series, King Ghazi's era is highlighted. As mentioned in part I, King Faisal I was enthroned as the King of Iraq on August 23, 1921. He became ill suffering from appendix pain on the same day (August 23) one year later (1922). The British doctors advised him to undergo appendectomy.

All sources agree that King Faisal I died in Berne, Switzerland in 1933. But not all sources agree on the exact date and the way the king had died. Some state that December 8 was his death date, others indicate that it was in September. The latter is accurate because his son, Ghazi, became the king in September. King Faisal died on September 7, 1933. Some sources indicated that as he was with Nuri As-Saeed and Rustum Haidar in Switzerland for a treatment, he suffered a sudden heart attack!

". . . with the untimely death of King Faisal, Iraq became like a ship without a captain. With the accession of King Ghazi to the throne in September 1933, the country became prey to military coups and tribal uprisings." King Ghazi inherited none of his father's diplomacy especially with the tribes. He was young and inexperienced, a situation that weakend the monarchy politically and encouraged the army to penetrate in politics.

Majid Khadduri, in his book "Independent Iraq" (2nd edition) stated that:

"The disillusionment of the army officers was reflected in voicing certain grievences such as that the army was excessively used to put down inspired tribal uprisings, while the politicians were to gain the fruits of victory. Why should not the army itself, it was whispered among the army officers, put an end to the quarrel and vices of the politicians and rule the country through a military dictatorship? "

The first problem faced King Ghazi was that of his marriage. He liked a lady by the name of Nimat (daughter of Yaseen Al-Hashimy) who was a friend of his sisters. Nuri As-Saeed (former Prime Minister until 1932) interfered because he did not want his opponent, Yaseen Al-Hashimy, to have the royal prestige and be called 'uncle' by King Ghazi. Nuri even requested the mediation of Prince Abdullah of East Jordan. He wanted him to marry his (first) cousin, Alia, who was living in Istanbul. After numerous attempts and prolonged pressures, King Ghazi married Alia Bint Ali on January 25, 1934.

King Ghazi's reign witnessed revolts and coup attempts in 1934, 1935 and 1936. In all of these events, the army enforced the law and order.

After resigning from his post as a Prime Minister, Nuri As-Saeed sought to return to power. Details on how he came back to power will be tackled in part 4 of this series. He became the Prime Minister in 1939, which was an exceptionally eventful year. The situation in Palestine was continuously deteriorating. During this year, the Palestine Conference took place, King Ghazi was killed and World War II began. Concerning the first event, it had become evident that the Jews wanted an independent state, which was a matter rejected by Arabs.

In March 1939 following Nuri’s return from the Palestine Conference, he became aware of an army plot, and so he was determined to overthrow King Ghazi. Nuri informed the King and the British Ambassador, Sir Maurice Peterson, that the fifteen-officer plot was connected with the ex-Prime Minister, Hikmat Sulaiman. In a telegram to the Foreign Office, Sir Peterson referred to these officers as ‘Bakr Sidqi’s Gangsters’. Sulaiman was arrested with the other officers and were sentenced to death. All the death sentences were later converted to long-term imprisonments.

“In Iraq the plot was widely seen as a fabrication by Nuri in order to avenge for Jaafar Al-Askari’s assassination (his brother-in-law) by Hikmat and Bakr entourage.”

The sudden death of King Ghazi came as a shock. He was killed in a mysterious car crash in the evening of April 3. His death was announced on the 4th. The mystery of his death can be summarized by the testimonies of those who were at the scene of the King’s death or have witnessed statements that can be argued as a motive for the King’s killing:

1. Rasheed Ali Al-Gailany,

“When I learned of the accident from Nuri As-Saeed, I went immediately to the Palace. There, I saw Doctor Sanderson working to cover the injured spot with gauze. I saw his injury, it was located in the rear of his head. Because the car was said to have hit an electric column, I expected it to hit the King’s head from the front.”

2. One of the Palace’s employees indicated that,

“The royal family’s primary physician arrived an hour after the accident, and the rest of the doctors arrived later. Nuri As-Saeed was the first to arrive in the Palace and joined Queen Alia and Prince Abdul Ilah."

3. Tawfeek As-Swaidy,“The Deputy of the British Foreign Ministry complained vigorously about King Ghazi’s behaviors as he publicly discussed the issue of Kuwait on his radio station from al-Zuhoor Palace."

King Ghazi was seen by his people as a nationalist hero for his suppression of revolts, his claim on Kuwait (which used to be part of Iraq before the British annexed it), his support for the Palestinian cause and his anti-British broadcasts from al-Zuhoor Palace’s radio station, which he established as a result of his love for radio broadcasting.

Sources:

1. "Independent Iraq" by Majid Khadduri [2nd edition], London 1960, pages 77-78

2. "Rashid Ali al-Gailani -- The Nationalist Movement in IRAQ 1939-1941 " by Walid M. S. Hamdi, London 1987

3. "Al-Iraq -- Shahada Siyaasiyya 1908-1930 " by Hussein Jameel (in Arabic), London 1987

4. " Al-Iraq -- Hawamish Minat-Tareekh walmuqaawama " by Abdur-Rahman Muneef (in Arabic), Lebanon and Moracco, 2004

5. " Tareekhul Wizaaraatil Iraqiyya -- Part I " [5th edition] by Abdur-Razzaq Al-Hasany (in Arabic), Baghdad 1978

-----------------------

5. Important Announcements

** Iraqi Women Historians are needed to join the writing/editing team to participate in the writing and editing of this IRAQ History e-newsletter. The candidate must posses a Masters degree with teaching experiences in Iraqi history and/or have been writing and publishing in the field. Please submit a biography and contact information by emailing it to historyofiraq@gmail.com

The 6th International Poetry Festival al-Mutanabbi 2006

From May 13 to May 20, 2006, in Zurich, Lucerne, Berne, Geneva and Lugano

In 2006 the “International Poetry Festival al-Mutanabbi” takes place for the sixth time. This is also the highlight of the regular events at the Swiss-Arab Cultural Center in Zurich. In Switzerland and Europe it is now the only poetry festival that has allowed the intercultural dialogue with Arabic poetry since its foundation in 2ooo.

After five years of existence the 6th “International Poetry Festival al-Mutanabbi” expands its programme to the three great language areas of multicultural Switzerland. This year, between May 13 and 2o, 2oo6, the eight multilingual festival readings and the panel discussion take place in the five cities of Zurich, Lucerne, Berne, Geneva and Lugano.

The theme of the 6th “International Poetry Festival al-Mutanabbi” 2006 is “Poetry and Politics”. The panel discussion about this year’s festival theme will be held at 12 o’clock on Sunday, May 14, 2006, in the Swiss-Arab Cultural Center in Zurich. It will deal with political subjects such as tolerance, democracy, human rights, equality, freedom, and other social topics that also form the subject of both oriental and occidental poetry.

From May 13 to May 20, 2006, Arab authors such as Murid Al-Barguti (Palestine), Helmi Salem (Egypt) and Kadhem Al-Hajaj (Iraq) meet Swiss colleagues, among whom Kurt Aebli, Sabine Wang, Kathy Zarnegin, José-Flore Tappy, and Alberto Nessi, and international writers such as Adnan Özer (Turkey), Daniel Leuwers (France), Matthew Sweeney (Ireland) and Luisa Castro (Spain), as well as Robert Schindel (Austria) and Ernest Wichner (Germany).

The festival readings are from Saturday, May 13, to Monday, May 15, at 8 p.m. at the Culture Market Rats (Zwinglihaus) in Zurich; on Tuesday, May 16, at 8.3o p.m. in the Old Casino in Lucerne; on Wednesday, May 17, and Thursday, May 18, at 8 p.m. in the Dampfzentrale in Berne; on Friday, May 19, at 8.3o p.m. in the Société de lecture in Geneva, and finally on Saturday, May 2o, at 9 p.m. in the Hotel Pestalozzi in Lugano.

The Poetry Festival “al-Mutanabbi” enjoys a good international reputation. We’ll be glad to have you as our guests at the 6th “International Poetry Festival al-Mutanabbi” in Switzerland. We’re at your disposal to answer your questions.

Zurich, May 21, 2006 (UNESCO Worldwide Poetry Day since 2000)

Al-Mutanabbi

(915-965 CE)

Abut-Tayyib Ahmed al-Mutanabbi was born in 303 Hijriyya (HJ)/ 915 CE in an area called Kinda in the City of Kufa (in today’s IRAQ). He had a rare talent in versifying poetry with no competitors in his lifetime!

He was given the family name of al-Mutanabbi because he claimed to be a prophet (Nabiy) while in the Samawa desert.

Abut-Tayyib traveled to Aleppo, Damascus and various cities in Egypt. In 350 HJ, he returned to Baghdad. Then traveled to Arjan and then to Shiraz in Iran, and finally arrived in Baghdad. In the early month of Shaaban, 350 HJ / 965 CE, he traveled to Kufa. While he was on the road in Kufa accompanying his son and a friend, a group of men passed by and harassed al-Mutanabbi. They mocked and challenged him into fighting. As a result of the fighting, al-Mutanabbi, his friend and son were all killed.

Al-Mutanabbi was the master of the exuberant panegyric, which is impossible to translate into adequate English. His (Diwan) collected poems are famous for their long-lived qasida. With a flowery style and changing away from the traditional Arabic qasida, Al-Mutanabbi stands out as the most important representative for the panegyric poetry.

For further reading and sources, visit http://www.poetrymagic.co.uk/poets/almutanabbi.html

(-------------------)

6. Acknowledgement

Many Thanks go to Abdul Kareem Hani for providing the pages from Abdur-Razzaq Al-Hasani's book, and to Wasan Sadiq for providing the pages from Majid Khadduri's book. Had it not been for the gracious help of many members of the Iraqi community in providing historic information, these IRAQ History e-newsletters wouldn't have become a reality.